The world’s oldest known bone tools have been unearthed at Olduvai Gorge, giving archaeologists and anthropologists deeper insight into the evolution of hominins and Homo sapiens.

A study released today describes an assemblage of bone tools made by early human ancestors. These tools provide clues on how archaic human species used knapping techniques to fabricate stone tools from hippo and elephant bones.

The “toolkit” uncovered by scientists from Spain, France, the United States, and the United Kingdom was unveiled in a layer of rock and soil known to be 1.5 million years old.

The study was led by Ignacio de la Torre with the CSIC-Spanish National Research Council.

This makes these bone tools the oldest discovered, preceding “other evidence of systematic bone tool production by more than 1 million years,” the team said.

The amazing discovery “sheds new light on the almost unknown world of early hominin bone technology,” the researchers wrote. Their findings are now out in the journal Nature.

The site of the discovery lies in northern Tanzania in Olduvai Gorge, made famous by the Leakey family and their discovery of early human fossils there. The bone tools were unearthed at the T69 Complex in the Frida Leakey Korongo West Gully.

The complex is ancient, and the stone tools discovered there are the oldest known to science.

“Radiometric and chronostratigraphic data firmly position T69 Complex site at 1.5 [million years old],” the researchers confirmed.

Stone toolmaking by early human ancestors dates to at least 3.3 million years ago. But prior to this discovery, the earliest bone tools were dated to, at most, around 400,000 years ago.

The area of the T60 Complex was once wet. Scientists know this because of the abundance of fossilized skeletal remains from hippos, crocodiles, and fish. More than 9,000 bones have been discovered there that can be identified as having come from a vertebrate animal.

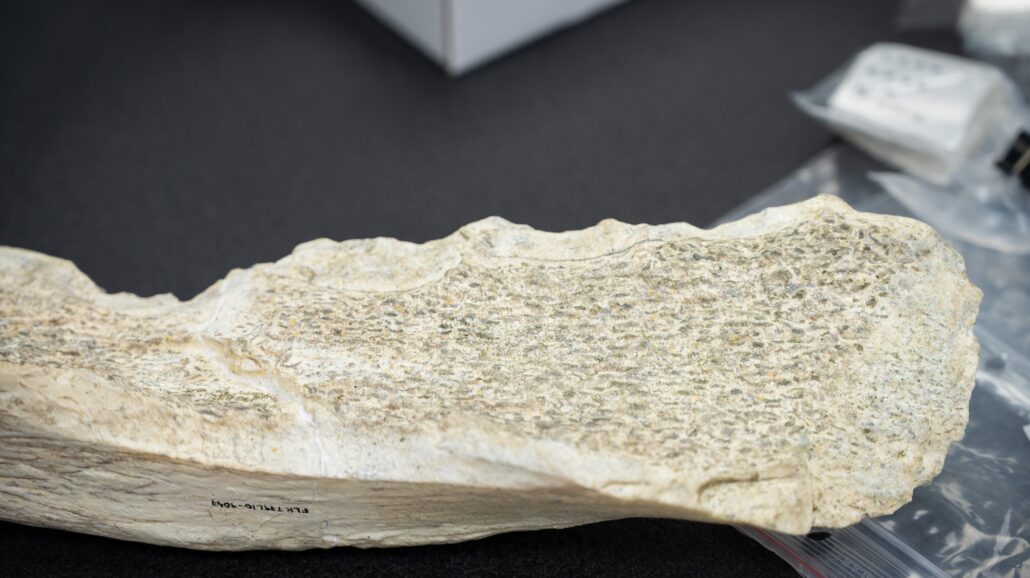

The bone tools discovered at the site have been clearly manipulated by hands, shaped in the manner that stone tools are shaped, through the process known as knapping. This tool-making method results in pieces being chipped or flaked off, creating sharp edges.

In total, 27 bone tools were discovered.

“All 27 bone tools were found in situ during excavation,” the team reported. Eight of the tools were fashioned from elephant bones, while six were made from hippopotamus bones. The tools were made from the animals’ leg bones.

The tools were fashioned with precision and care, the team says.

“When shaping bone tools, the T69 Complex knappers invested substantial effort in first producing invasive flake removals to shape the tool and, subsequently, regularizing the resulting edges via trimming,” De la Torre et al. note in the study.

They believe the toolmakers use “handheld hammer stones” to chip away at the bones and sharpen their edges.

Our species, Homo sapiens, is believed to have evolved in Africa about 300,000 years ago. That means these stone tools were crafted by a species of archaic humans well before Homo sapiens emerged.

Despite being a more primitive species of early hominin, the evidence reveals that the prehistoric bone toolmakers were “culturally innovative, able to transfer and adapt their stone knapping skills to a new raw material” the researchers argued.

A separate recent investigation revealed evidence that early human ancestors were far more capable of adapting to changing conditions than originally thought.

That study, also based in Olduvai, revealed signs showing how Homo erectus learned to adapt to a changing regional climate.

The archaeologists said they uncovered the butchered remains of animals and the tools Homo erectus used to butcher them.

The assemblage of tool use evidence matches the geological record of wet and dry periods, indicating that Homo erectus used this site repeatedly to survive harsh dry spells. That study’s authors argue that this experience could have primed the species to break out of Africa and begin its expansion in Asia.

Park Info

Park:

Olduvai Gorge

Location:

Tanzania

More information: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-08652-5