Tourism’s final frontier is getting more popular by the year, raising concerns about environmental impacts in the absence of any strong managing authority.

Antarctica is considered international territory by treaty, though some nations claim parts of it. Visitors are technically governed by the laws of their home jurisdictions, but every year rising numbers of multinational group tours arrive on the polar continent to bask in its frigid climate, unique wildlife, and wild terrain.

As tourism to Antarctica grows, the tour operators responsible for delivering thousands of visitors to this remote land every year have been left to govern the influx themselves, and it’s uncertain how long this situation can last as visitor numbers continue to swell each year.

The treaty system cobbled together to guide activity on Antarctica is partly to blame for this atmosphere of uncertainty, said Elizabeth Leane, Professor of Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania.

“The [Antarctic Treaty System] has no instrument that is specifically directed at regulating tourism, although this has certainly been raised,” Leane told Public Parks. “Although many hortatory resolutions are passed, it is difficult for the ATS to pass binding measures specific to tourism given the consensus-based process.”

Leane says it will be some time before government parties to the Antarctic Treaty System come up with a more systematic, organized way of regulating tourism to the region. “There seems to be a strong appetite for some kind of more systematic, wholistic approach to regulation of tourism through the ATS,” she said, “although given its pace we are probably looking at a five to ten-year timeframe.”

An increasingly popular destination

Experts say that tourism in Antarctica has exploded by a factor of ten over the past two decades. While the global COVID-19 pandemic put a dent in activity, the resurgence of global tourism post-pandemic is being felt in the southernmost continent, as well.

The 2023-2024 tourism season in Antarctica may be one for the record books.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), about 75,000 tourists visited Antarctica in the season just before the pandemic hit. Visitor numbers are now eclipsing this prior high-water mark. IUCN says about 105,000 tourists traveled to Antarctica during the 2022-2023 season.

Most visitors to Antarctica hail from the United States, but the number of visitors from other nations is growing rapidly. IUCN says that the number of Antarctic tourists from China expanded by 98 percent from 2015 to 2020. German visitor numbers swelled by over 120 percent over the same period.

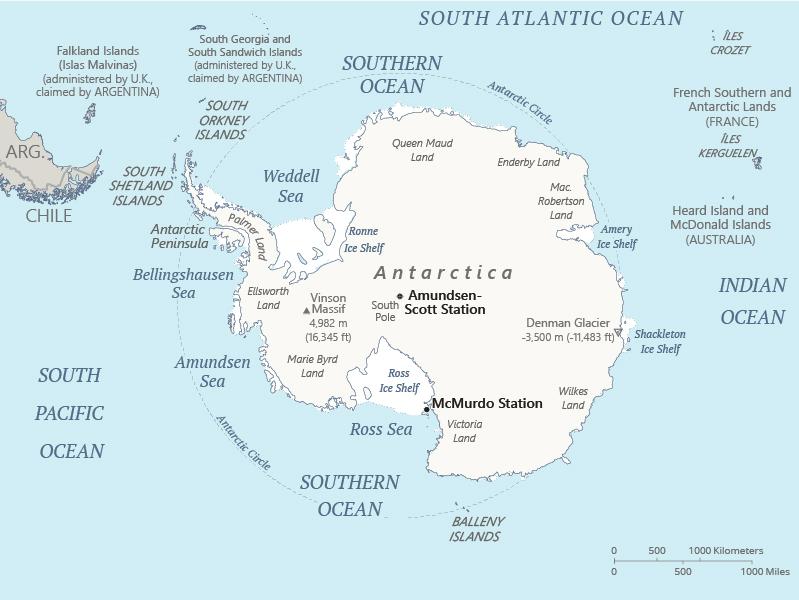

Tourists reach Antarctica either by cruise ships or through special charter tour arrangements. The vast majority visit the Antarctic Peninsula from boats leaving ports at the southern tip of South America. These are the more traditional ways to visit the continent as a tourist and not a scientist or government worker, but recently tour packages are offering visitors the chance to explore Antarctica far more deeply than what was typical in the past, but for a hefty price.

Adventure Consultants, a New Zealand-based tourism operator, sold tickets for a 2023-2024 season overland trek from Antarctica’s shores to the South Pole. For 66 days guests will ski to the South Pole accompanied by guides for a price tag of $85,000 each.

“It is an expedition that will allow you to join an elite group who have undertaken this adventure under their own power,” the company says in a brochure. Adventure Consultants also offered the option of joining a different, shorter route for a 54-day trek to the Pole for $82,000.

The new Everest?

This rise in this so-called deep-field tourism in Antarctica has been compared to the explosion in adventure tour companies in the late 1990s guiding amateur mountain climbers to the summit of Mt. Everest. Evan Bloom, Senior Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and a close observer of the rise in Antarctic tourism, doesn’t think the level of danger in Antarctic tourism is comparable to a trek to the top of Everest, but he agrees that more needs to be done to monitor and control Antarctic tourism, including deep-field tours.

Still, despite general concerns over tourism’s impact on the Antarctic environment, Bloom argues that such worries are overblown. “Deep-field tourism is rising, but the environmental impacts of this are relatively limited given the huge size of the continent,” he said.

IUCN doesn’t share his optimism.

“As the Antarctic tourism industry grows and diversifies, the severity of its negative environmental impacts is likely to increase,” the organization warns in a 2023 research paper. “If left unchecked, these impacts will be exacerbated by the effects of climate change.”

Leane argues that the climate is being hit hardest by the rising numbers of tourists visiting Antarctica.

“For me, the greatest impact of Antarctic tourism on Antarctica’s environment is probably from emissions” from all the ships and planes traversing the region, Leane said. She argues that this is pretty typical for tourism in general, but Leane agrees that the risk of other kinds of negative impacts on the continent increases with the rising visitor numbers.

Some threats Leane says she’s keeping an eye on include “invasive species, disturbance of wildlife, noise pollution, whale strikes, damage to soil due to trampling, black carbon, risk of fuel spills” and more.

Bringing it all under control

Outside experts and ATS member governments alike agree that a better management strategy is needed to control the Antarctic tourism boom and the environmental consequences that will come from it.

Given the management vacuum that exists today, it’s largely been left to an association of Antarctic tour operators to devise a set of rules to police themselves. Bloom and Leane both agreed that the current de-facto regulator of Antarctic tourism isn’t governments or the treaty system, but rather the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators (IAATO).

Bloom says this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but he doesn’t believe this situation can stand forever.

“In my view, IAATO is doing a relatively good job, but it would make sense for the treaty parties to play a more active role in regulating tourism given the significant rise in shipborne tourism, which has a lot of environmental and safety implications,” Bloom said. “In other words, ultimately it is for governments to regulate, not just industry.”

Leane clarified that ATS treaty system governments do play a role in regulating tourist visits to Antarctica. It’s the governments that grant permits to the tour operators—technically, the operators are forbidden from venturing to the continent without some government oversight. But from there, it’s left to the operators and IAATO to control the traffic and behavior of visitors.

Some governments have floated the idea of capping the number of tourists allowed to visit Antarctica each year. IAATO opposes this. Leane said to keep the heavy hand of government intervention away, IAATO is constantly investigating the impacts on Antarctica from tourism and proposing new rules or practices to address them. “IAATO is always introducing new recommendations or requirements in response to evidence,” she said.

Ongoing talks on how best to manage this massive public land

Still, Leane said governments are increasingly actively debating how best to manage Antarctic tourism during their Antarctic treaty talks. Bloom confirmed this. “There are efforts underway for the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings to play a more significant role, and that would be a good thing,” he said.

Though visitation is regulated to an extent, Antarctica is effectively one massive public land that isn’t protected by strong conservation laws. Given that no single government controls Antarctica and governments collectively can’t agree on building a better tourism and environmental management regime, Leane warns that this murky picture will be around for some time. But those who do control how travelers enjoy tourism’s final frontier are making the best of a difficult situation, she says.

“On the whole, I would say that at present the industry is very well managed,” Leane said. “This is not to say that every operator is equally good and that some don’t push boundaries. And growing numbers and diversification of activities will put pressure on the industry going forward, so the action in the ATS is welcome.”

©2025 Public Parks