It turns out that the world’s southernmost continent is teeming with life—we just need to know where to look.

A new study published yesterday finds that Antarctica, a protected international territory governed by the Antarctic Treaty, is far more biodiverse than science previously recognized. The continent’s biodiversity is mainly trapped in its frozen soils, according to researchers based in Germany.

Their discovery is published in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology. Professor Dirk Wagner of the University of Potsdam said his team was surprised by the abundance of life discovered, given the harsh conditions in which this microscopic life must survive.

“Here we reveal unexpectedly abundant and diverse microbial community even in these driest, coldest, and nutrient-poorest of soils, which suggests that biodiversity estimates in Antarctic soils may be greatly underestimated,” Wagner said.

Wagner and his team say this study only marks the beginning of a deeper investigation into the micro-biodiversity of Antarctica.

Their findings were revealed through DNA sequencing. The sheer abundance of microscopic species discovered astounded them, they said.

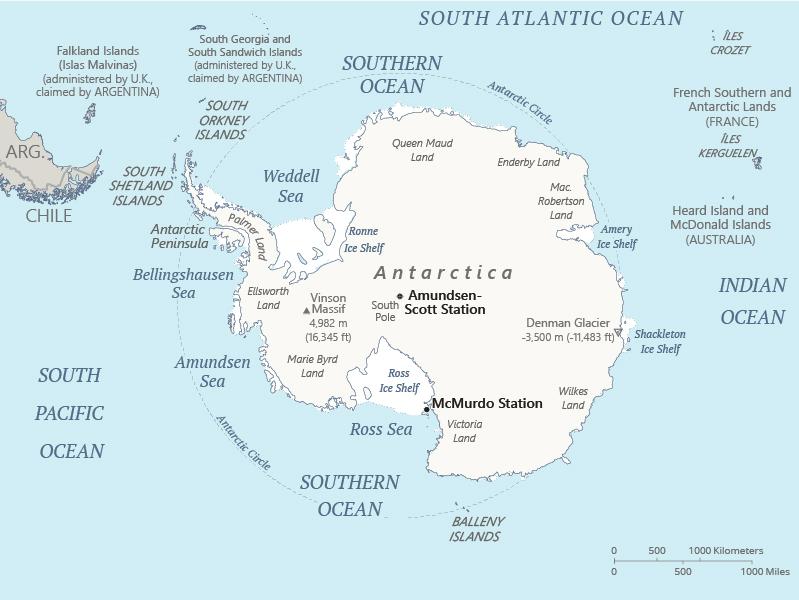

From just 26 soil samples, the team uncovered “2,829 genetically defined species,” they wrote. The soil samples were collected in front of a retreating glacier at the Larsemann Hills close to the shoreline at Prydz Bay. The location is close to Davis Station, an Australian Antarctic research base.

Among the lifeforms discovered, the team found species of bacteria and a type of fungus that thrives in cold conditions. They also discovered numerous species of algae.

Wagner said the presence of such a huge volume and variety of microbial life is a sign of succession at work.

Succession is the process whereby the hardiest of living organisms colonize new land first, gradually transforming the habitat to become more suitable to more fragile yet higher-order types of life. For example, a newly formed volcanic island will be colonized by plants evolved to cling to rock and survive with little water. These plants then gradually break down the rock to create soil, permitting shrubs and even trees to colonize next.

Wagner speculates that the colonies of microscopic bacteria, fungi, and algae represent later generations of life that were able to colonize the harsh environment of Antarctica thanks to earlier pioneers.

“By focusing on both current and past lineages of microbes, our study shows how colonization and environmental alteration through ecological succession helped change the extreme habitat of Antarctica’s Larsemann Hills, making them gradually more hospitable to the current considerable diversity of life,” Wagner said.